|

|

Galileo's Evidence and Obstacles to Learning

Galileo's experiences in 1610 and the following years should be understood by everyone because they show how easy it is to

misunderstand nature and ourselves. It shows that educated and intelligent people can go through life in a state of

ignorance about important matters. And it shows that they tend to perpetuate their ignorance by ignoring good evidence

that would require a modification of their beliefs.

For many centuries, scholars and leaders believed that Earth was the center of the universe and that heavenly bodies

revolved around Earth. This false belief dovetailed with related beliefs or "complementary illusions." For example,

it was believed that all "heavenly bodies" were comprised of a special heavenly material, that the bodies had an innate

tendency to move in circles around Earth, and that the heavens in general had a perfection not found on Earth.

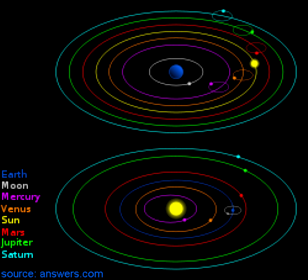

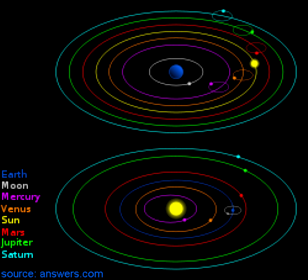

These beliefs were complementary with prevailing religious beliefs in Galileo's time and location. This geocentric view

is shown in the upper-right figure. It includes refinements by Ptolemy that made it consistent with the irregular retrograde

motions of planets. It was an accepted "truth" in spite of many

unanswered questions. (e.g. Why do heavenly bodies have an innate tendency to move around Earth?)

In 1610 Galileo found various evidence showing that the geocentric view of the heavens was probably wrong.

About 70 years earlier Copernicus had concluded that the geocentric view might be wrong. He suggested the view shown

in the bottom figure, and similar views had been suggested over the previous 1500 years. But most astronomers, philosophers,

and others responsible for shaping

public opinion continued believing the geocentric view. In 1610 Galileo made observations with his newly improved

telescope that were instrumental in eventually changing people's minds to the Copernican view. While observing Jupiter,

Galileo was able to determine that four bodies were moving around this planet, and he thought they were probably moons

orbiting Jupiter the way our moon orbits Earth.

The figure, above-center, is the first known documentation of Galileo's findings.

His drawings show the changes in locations of the moons around Jupiter. The picture, above-left, shows recent

images of Jupiter and its four largest moons that Galileo first observed 400 years ago. Initially, scholars doubted Galileo's

observations because they were sure all heavenly bodies must move around Earth. Galileo's observations of Venus also disagreed

with the geocentric view and agreed with the Copernican view. Galileo observed that Venus has phases like the phases of our

moon (i.e. full, gibbous, half, crescent, and new phases). The geocentric view cannot explain this range of phases for Venus.

Surely Galileo's new evidence helped some people reach better conclusions about the cosmos, but most could not stop thinking that

Earth was at the center of things. Eventually, Galileo was arrested and forced to retract his support for the Copernican view. His

experiences show that established beliefs in society can survive in spite of evidence showing they are probably wrong. This

should make one wonder what currently established beliefs might be wrong. This website shows why various established views of

important matters are less likely to be correct than their adherents and the populace believe. A purpose of the website

is to encourage an examination of prevailing beliefs and a determination of realistic uncertainties for the beliefs.

Relevant to this discussion is Leonardo da Vinci's observation that "There is no higher or

lower knowledge, but one only, flowing out of experimentation." Experimental results often point directly to the truth

about our universe, but not always. For centuries people had been making careful observations of the sun and other

heavenly bodies moving around Earth. Frequently the experimentation led to false conclusions such as epicycle orbits to

explain the retrograde motions of planets. Also, we know from Copernicus and others that it is possible

to use good reasoning to reach plausible conclusions without conclusive evidence. The Copernican view made sense and had a good

probability of being correct even before it was supported by Galileo's experimental evidence.

It easily explained the retrograde motions and the seasonal changes on Earth, and it did not require inexplicable heavenly matter.

Thus, when trying to determine how nature works, we need both experimental evidence and good reasoning so our

conclusions reflect all related evidence and the uncertainties.

|

|